UK money trends suggesting "stagflation"

UK monetary trends correctly predicted recent economic strength but are now signalling a second-half slowdown. The earlier buoyancy, however, is likely to sustain upward pressure on inflation into 2018, suggesting a difficult “stagflationary” backdrop for the MPC and markets.

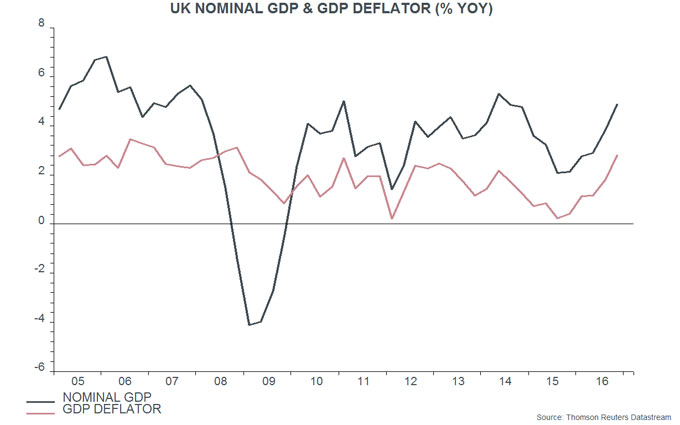

The big story in last week’s fourth-quarter GDP report was not the expected upward revision in quarterly output growth from 0.6% to 0.7% but rather a sharp increase in nominal GDP expansion – annual growth rose to 4.9%, the fastest since 2014 and up from just 2.1% a year earlier. This strength has been driven by an acceleration in the GDP deflator, which rose by 2.8% in the year to the fourth quarter, the largest annual gain since 2008 – see first chart. This ought to be ringing alarm bells at the Bank of England, since the GDP deflator is a broad measure of domestically-generated inflation and is not directly affected by changes in import costs.

Nominal GDP numbers, admittedly, are often revised significantly but the suggested strength is consistent with recent higher-than-forecast tax receipts and undershooting public sector borrowing.

Faster nominal GDP expansion was predicted by an acceleration of narrow and broad money – measured by non-financial M1 and non-financial M4 – in 2015-16. Annual growth of the two measures has moderated since September 2016 but remains solid by post-crisis standards, at 9.2% and 5.5% respectively in January – second chart. Allowing for the usual six to 12 month lead, this suggests that nominal GDP growth will rise further in the first half of 2017 and remain elevated into year-end, and probably beyond.

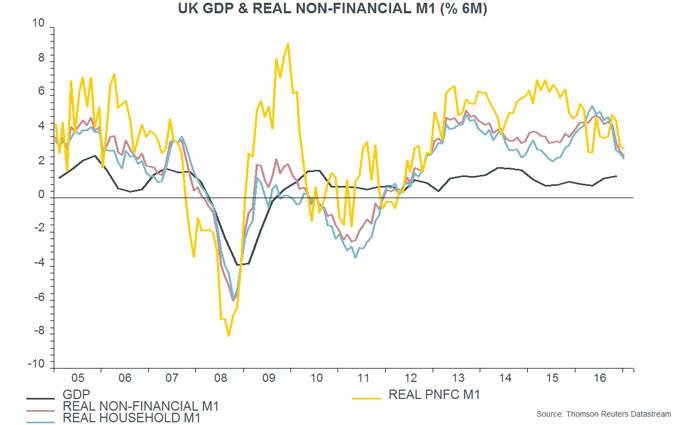

The question, then, is how nominal GDP growth will divide between output expansion and inflation. The preferred monetary measure here for forecasting fluctuations in economic activity is the six-month rate of change of real (i.e. consumer-price-deflated) narrow money. This measure peaked in June 2016 and has fallen sharply since October, to its lowest since 2012, reflecting a pick-up in six-month CPI inflation as well as lower nominal money expansion – third chart. This slowdown suggests that two-quarter output momentum is at or close to a peak and will decline during the second half of 2017. Real narrow money, however, is not yet signalling outright economic weakness – the six-month change is still far from turning negative, as it did before the 2011-12 “double dip” scare.

Household and corporate (PNFC) narrow money trends are informative about prospects for consumer spending and business investment respectively. Six-month growth rates of real household and PNFC M1 were similar in January – fourth chart. Both have moderated recently but have yet to signal significant spending weakness.

The suggestion that nominal GDP expansion will remain firm while output growth will moderate implies further upward pressure on GDP deflator inflation. Such strength would undermine the MPC’s claim that rising CPI inflation is entirely explicable by sterling weakness and commodity price gains, with no impact from domestic capacity pressures or “second-round” effects.

How would the MPC respond? The market judges that the Committee will have a strong aversion to raising rates during the Brexit negotiation process, almost irrespective of inflation or currency developments. Even Governor Carney, however, may believe that policy credibility has been stretched to its limit; he may, in any case, be running out of new excuses to defend the MPC’s ultra-loose stance.

Reader Comments