Inflation leading indicators still benign

Three indicators that signalled the 2021-22 global inflation spike and reversal continue to suggest a favourable outlook.

G7 annual broad money growth led the rise and fall in annual consumer price inflation by about two years, consistent with the rule of thumb suggested by Friedman and Schwarz.

The global manufacturing PMI delivery times index – a measure of supply constraints / shortages – led by about a year.

The annual rate of change of commodity prices – as measured by the energy-heavy S&P GSCI – led by nine months.

Chart 1 overlays the three series, with respective leads applied, on G7 annual inflation.

Chart 1

The latest readings of all three are below their averages over 2015-19. Those averages were associated with average headline and core inflation of below 2% (i.e. allowing for the stated lead times).

Directionally, the suggested influence of the three indicators over their respective forecast horizons is down for commodity prices, sideways for delivery times and up for broad money growth. The latter recovery, however, is from extreme weakness.

In combination, the level and directional signals suggest that inflation will move down into early 2026, with limited recovery over the following year.

Tariffs may affect the profile but are unlikely to change the story. A mechanical boost to US prices in Q2 / Q3 will drop out of the annual inflation rate a year later. The effect may be to push out the inflation low from early 2026 to later in the year.

Tariffs could have a larger and more sustained impact by snarling up supply chains and disrupting production, resulting in delivery delays and shortages.

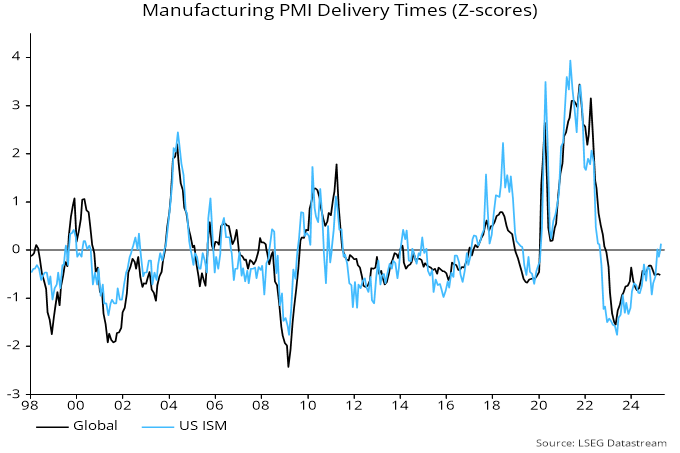

The global manufacturing PMI delivery times index currently remains below its long-run historical average, as well as its average over 2015-19 – chart 2.

Chart 2

Delivery times have risen in the US but the ISM manufacturing supplier deliveries index is only back to its average.

Reduced exports to the US will increase excess supply in the rest of the world, depressing delivery times and pricing power, balancing upward pressure in the US.

Any tariff boost to inflation will persist over the medium term only if associated with a rise in broad money growth. This could occur if central banks ease policies excessively, because of actual or feared economic weakness, or perhaps to limit upward pressure on currencies. Alternatively, inflation worries could deter non-bank purchases of government debt, resulting in banks being required – voluntarily or otherwise – to fund a larger proportion of (wide) fiscal deficits, creating money in the process.

Such scenarios are plausible but the inflationary effects of any broad money acceleration would be unlikely to appear before 2027.