Is the high yield rally sustainable?

The yield spread over Treasuries of the ICE BofA US corporate high yield index rose from 310 bp at end-December to a peak of 599 in early July. It has since retraced more than half of this move. Was the early July peak a major top, with a further decline in prospect? This seems unlikely, for several reasons.

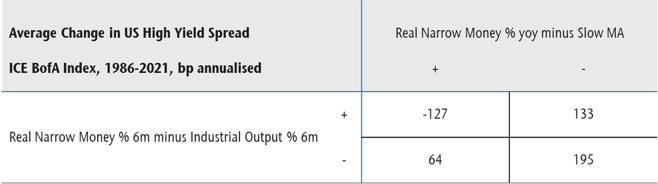

First, the “financing gap” of non-financial corporations – the difference between capital spending and domestic retained earnings – is a long leading indicator of credit spreads and has widened significantly in recent quarters.

Chart 1 shows an expanded measure of the gap including financing required for net equity purchases. This measure moved from a negative position (i.e. a surplus) in Q1 2021 to 4.3% of GDP in Q1 this year, reflecting a strong rise in capital spending – including on inventories – and a pick-up in equity buying.

Chart 1

The expanded financing gap rose above 4% of GDP in 1989, 1998, 2000, 2006 and 2019. The high yield spread subsequently increased to at least 850 bp. (The gap also exceeded 4% in Q4 2017 but was temporarily inflated that quarter by revenue shifting by corporations to take advantage of lower tax rates from 2018 – there was an offsetting surplus in Q1 2018.)

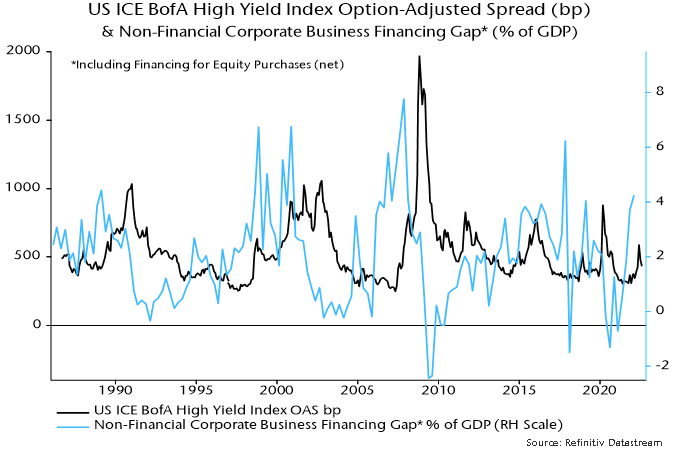

Secondly, the high yield spread correlates contemporaneously with the credit tightening balance in the Fed’s senior loan officer survey – chart 2. This rose sharply between April and July and special questions in the July survey suggest a further increase in H2 – see previous post for more details.

Chart 2

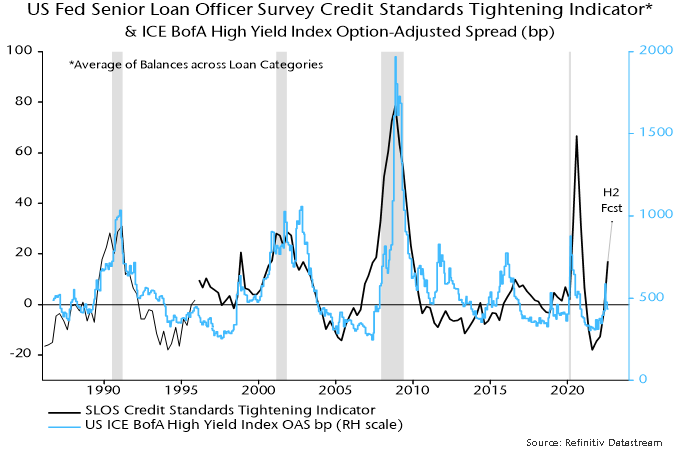

Thirdly, the stockbuilding cycle is judged here to have entered a downswing that may – based on the average length of the cycle – extend into mid to late 2023. Historically, the high yield spread has usually peaked late in the downswing or even after the trough – chart 3. The 2011-12 downswing was an exception but the early surge in the spread on that occasion probably reflected credit market contagion from the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis.

Chart 3

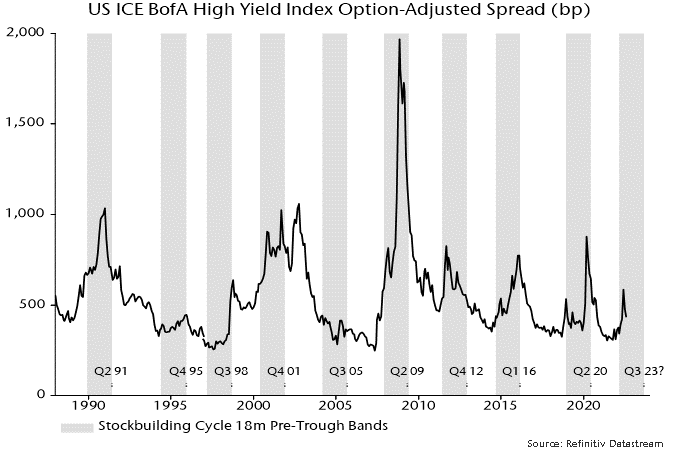

Finally, the two measures of global “excess” money tracked here remain negative, a condition historically associated with a widening spread on average – table 1. The first measure – the gap between six-month real narrow money and industrial output momentum – may turn positive during H2 but the second measure – the deviation of 12-month real momentum from a moving average – will almost certainly remain negative. That combination has also been negative for credit historically.

Table 1