Inflation worries are premature

Recent policy upheavals may eventually prove inflationary but near-term risks are judged here to remain on the downside.

In common with conditions preceding the 2021-22 inflation upsurge, recent developments combine elements of a negative supply shock (tariffs, supply chain disruption, reduced US labour supply) with a potentially major demand boost (ramped-up European defence / infrastructure spending, US tax cuts).

The difference is that the earlier episode involved an immediate surge in money growth as fiscal blowouts were financed by money creation and central banks added fuel to the fire by slashing rates and launching large-scale QE.

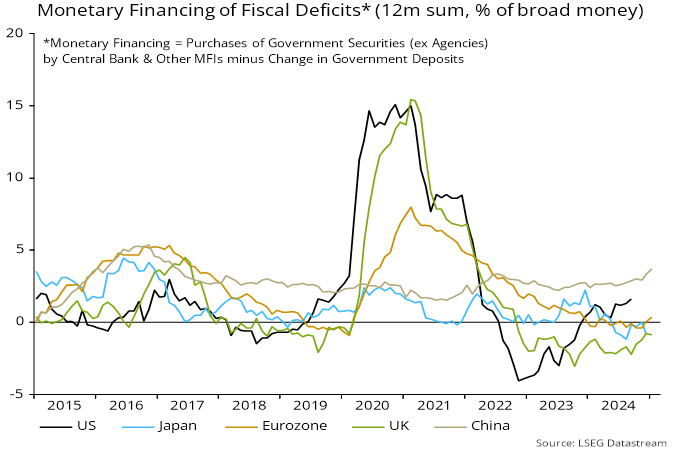

Current fiscal developments will plausibly boost money growth as deficit financing needs expand and / or central banks and commercial banking systems are required to provide a greater proportion of funding to limit upward pressure on government borrowing costs. Unlike 2020, this will play out over years rather than months, however. Monetary financing is currently contributing little to G7 broad money growth, though has picked up in China – see chart 1.

Chart 1

Central banks, meanwhile, have turned more cautious rather than stepping on the gas, and policy uncertainty is suppressing business / consumer confidence, which may be reflected in less money growth support from private sector credit demand.

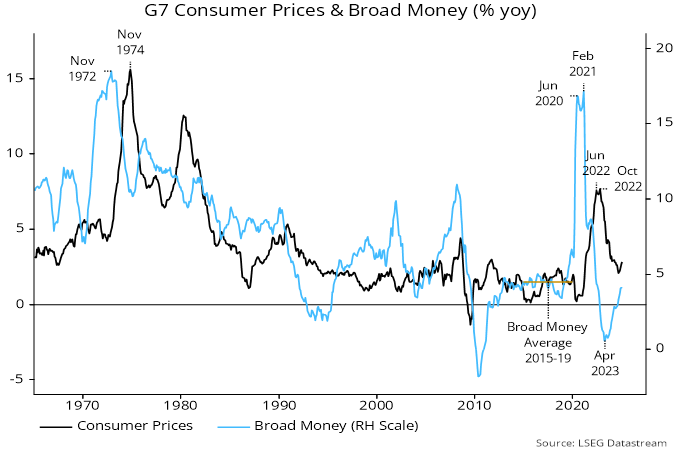

G7 annual broad money growth recovered further in January but, at 4.1%, is still below its 2015-19 average, which was associated with sub-2% headline / core inflation averages – chart 2.

Chart 2

Six-month growth is stronger, at an annualised 5.2%, but hardly ringing inflationary alarm bells.

Has potential economic growth fallen since the 2010s, so that a given level of money expansion is more inflationary than then? Arguments are mixed – possibly weaker labour supply expansion versus AI deployment and higher European investment spending.

The monetarist rule of thumb of a roughly two-year lag between changes in money growth and their maximum impact on inflation conceals significant historical variation but has worked near perfectly in recent years.

With annual money growth bottoming in H1 2023 and only now returning to a “normal” level, the suggestion was that annual inflation rates would fall further in 2025 and remain low through 2026.

Tariff hikes will have a price level impact but second-round effects are unlikely given the restrictive influence of earlier monetary weakness. A (small) lift to annual inflation this year should, therefore, reverse in 2026, raising the possibility that the lag between the H1 2023 money growth low and associated inflation low will extend to around three years on this occasion (still well within the historical range).

I think we should consider greater short term inflation sensitivity to fiscal policy. In scenarios where a very large proportion of growth is coming from the government sector.

Possibly exacerbated by the late cycle economic environment.

It is likely to be short lived and should be ignored by policy makers. History tells us, however, this almost never happens.

Policy is usually held too tight until labour market weakness accelerates suddenly, causing very rapid rate cuts …